Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

A congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM) is an abnormal part of the fetal lung tissue that forms during pregnancy. CPAMs are rare and occur in approximately 4 out of every 10,000 live births worldwide.

About Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

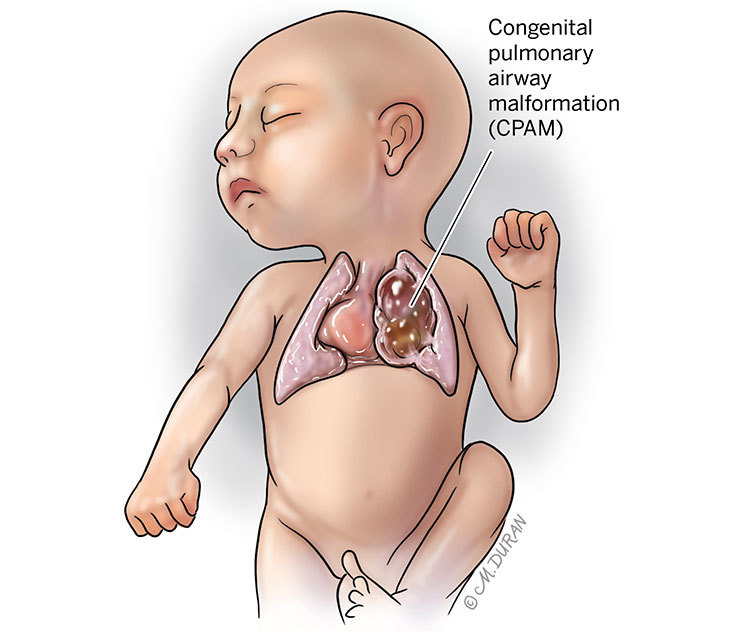

At around 5 to 6 weeks of gestation, the small air tubes (bronchioles) that connect the larger air tubes to the ending air sacs (alveoli) in the lungs may fail to develop properly in a baby. This results in small, and sometimes large, cysts (sac-like pockets that contain fluid) in the affected lung. This is known as a congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM), formerly referred to as a congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM). In approximately 98% of all cases, this occurs in only one of the baby’s lungs. Each lung is composed of two or three smaller units called lobes. CPAMs are usually limited to one lobe within the lung, and the blood supply to the CPAM typically remains the same as the rest of the normal lung. Developing a CPAM is slightly more common in male fetuses than in female fetuses. The different types of CPAMs are classified according to their appearance on an ultrasound.

Types of CPAMs include:

- Type I (macrocystic) make up 50% of cases and consists of one, or multiple, large (2-10 cm in diameter) cysts.

- Type II (microcystic lesions) make up 40% of cases and consist of multiple smaller (less than 2 cm in diameter) cysts.

- Type III (solid-appearing lesions) make up the remaining 10% of cases and appear as solid masses.

Other problems that can occur in the fetal lungs may include:

- Bronchopulmonary sequestration (BPS) occurs when a piece of abnormal lung tissue, typically a solid part, doesn’t function like normal lung tissue. This portion receives its blood supply from the main blood vessel in the fetal body (the aorta), which helps the mass grow in size.

- Hybrid lung lesions can be both cystic and solid, similar to a BPS, and receive their blood supply from the aorta.

- Bronchial atresia occurs when the main air tube (bronchus) does not develop across the whole lung, causing one or both of the fetal lungs to appear white on an ultrasound.

Symptoms of Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

At birth, some babies born with CPAM will not be able to breathe effectively due to the large size of the mass in their chest. If babies are unable to breathe effectively on their own, it may affect their heart function. These babies need immediate intensive care to stabilize them before the mass can be removed through surgery.

Causes of Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

The cause of a CPAM remains unknown.

Complications Associated With Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

If a CPAM is large enough to shift the heart over to the other side of the chest, additional problems may arise in the fetus. One way to predict the outcome is to use ultrasound to measure the size of the CPAM and compare it to the size of the fetal head (cephalic to volume ratio, or CVR). A value greater than 1.6 indicates a large CPAM. CPAMs that move the heart over in the chest can be associated with swallowing difficulties in the fetus. This can lead to excessive fluid surrounding the outside of the fetus in the amniotic sac (polyhydramnios), which occurs in approximately one-fourth of all cases.

In approximately 10% of cases, a more serious problem may occur in the fetus known as hydrops. In this scenario, fluid can build up in the abdomen (ascites), around the lungs (pleural effusions), around the heart (pericardial effusion), and in the skin (subcutaneous edema). The placenta can also become thick with fluid (placentomegaly) and there can be excess fluid in the sac surrounding the fetus (polyhydramnios). If left untreated, hydrops can become a sign of the impending death of the fetus.

Problems with other organs, such as the heart, are commonly associated with Type II CPAMs. Other fetal anomalies are rarer and more commonly associated with Type I and Type III CPAMs. Due to this, a complete assessment of the fetal anatomy should be undertaken by an experienced physician using ultrasound. A fetal MRI and a fetal echocardiogram (special heart ultrasound) may also be useful in assessing the fetal anatomy. The presence of chromosomal abnormalities in fetuses with a CPAM are very rare.

Long-term studies of babies with CPAMs that have not been removed after birth have revealed a higher chance for infection in the CPAM and a slight increase for the development of cancer. For these reasons, your baby will be assessed by a pediatric surgeon within in the first few weeks after birth who may order a CT scan for your baby at around 2 to 3 months of age. A decision will be made regarding the removal of the CPAM, which occurs between 3 to 6 months of age using a small telescope (thoracoscopy) placed in the baby’s chest.

Diagnosing Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

A CPAM is usually found at the time of an anatomy ultrasound at around 20 weeks (5 months) of gestation. The mass may appear as either a collection of fluid-filled cysts in one of the fetal lungs, or it can appear more solid and whiter (echogenic) than the lung around it. If the CPAM is large enough, it may push the fetal heart over to the other side of the chest.

Pregnancy With Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

If the fetus develops excess fluid in the sac surrounding the fetus (polyhydramnios), this can lead to maternal discomfort and, in some cases, problems with maternal breathing. In these cases, the fluid can be temporarily drained from the sac around the fetus through a procedure known as amnioreduction. During this procedure, a needle is placed into the uterus using ultrasound for guidance. The needle is then connected to a tube and the excess fluid is drained over a 20- to 30-minute period of time.

If a fetus develops both hydrops and placentomegaly, a condition known as mirror syndrome can occur in the pregnant mother. In this situation, the mother begins to mirror the findings in her fetus. In severe cases, this can lead to retention of fluid in the pregnant mother and breathing difficulties to arise due to fluid buildup in her lungs. High blood pressure can also occur and become a complication. The only treatment for maternal mirror syndrome is delivery of the fetus. After delivery, the mother’s symptoms will resolve over several days.

After the initial evaluation, you will be scheduled for ultrasounds every 1 to 2 weeks to assess the size of the CPAM and to check for evidence of hydrops. Most CPAMs stop growing after around 26 to 28 weeks (6.5 to 7 months) of gestation. At this point, your doctor may perform your ultrasounds every 3 to 4 weeks. If your baby’s CPAM is large, a fetal MRI may be ordered. You will likely also be scheduled for a prenatal consult with a pediatric surgeon to help determine how the CPAM will be managed after birth.

A vaginal delivery is safe for a baby with a CPAM. You will be allowed to go into spontaneous labor. In some cases where the CPAM remains large near the time for delivery, your labor may be induced so that the neonatal and surgical teams can be immediately available when the baby delivers in case your baby has any problems with breathing. In some cases where the CPAM is large, you will be asked to deliver in a hospital with a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Your baby may require that a breathing tube be placed in their trachea (windpipe) to provide oxygen (endotracheal intubation). This will be undertaken by a neonatologist in the delivery room. The baby will then be taken to the neonatal intensive care unit. When the neonatal team feels that the baby is stable, the pediatric surgeons will take your baby to surgery to remove the CPAM.

If the baby does not require oxygen or assistance with breathing, your baby may be discharged and a return visit may be scheduled with the pediatric surgeon to later discuss the removal of the CPAM once your baby is at a few months of age.

If the CPAM in your baby is small, you may be allowed to deliver at your local community hospital since your baby should not experience any breathing problems after birth. You would then be contacted by a nurse to schedule your baby to be assessed by a pediatric surgeon after the baby has been home for a few weeks.

Treating Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation

In some cases of a large cyst in the CPAM, hydrops may develop. In these cases, your doctor may talk with you about placing a shunt (small tube) into the cyst to drain it into the fluid area outside the fetal chest. This plastic tube is placed with local anesthesia. Once your doctor guides it into place using ultrasound, it will remain in place for the rest of your pregnancy and be removed soon after birth.

If your baby’s CPAM has a CVR greater than 1.6, your doctor may offer you treatment with steroids. This involves two injections of a medication known as betamethasone into your arm or hip two days apart. This treatment of two injections may be performed every week for three weeks during which the CPAM should stop growing.

If the CPAM remains large despite the use of steroids, you may be scheduled for a C-section so that pediatric surgeons in a nearby operating room are prepped and ready to remove the CPAM right after birth to fix your baby’s breathing problems. In some cases, this may be undertaken by an “EXIT-to-resection” procedure. This is a “partial C-section” in which the baby is delivered but not separated from the umbilical cord after you have been put to sleep using local anesthesia. The baby will still receive oxygen from the placenta during this part of the operation and the pediatric surgeon can begin the operation to remove the CPAM.

Open fetal surgery has been done in the past in cases when the fetus was very premature and hydrops was developing. This is rarely done today as the use of steroids has become more widespread. Steroids have even reversed fetal hydrops in some cases.

Evaluation After Birth

After birth, your baby may undergo surgery to remove the CPAM. After surgery, your baby can go home when they are able to breathe sufficiently and eat enough to maintain and gain weight. The long-term outcome for babies who undergo surgery to remove the CPAM is excellent.

Care Team Approach

The Comprehensive Fetal Care Center, a clinical partnership between Dell Children's Medical Center and UT Health Austin, takes a multidisciplinary approach to your child’s care. This means you and your child will benefit from the expertise of multiple specialists across a variety of disciplines. Your care team will include fetal medicine specialists, obstetricians, neonatologists, sonographers, palliative care providers, fetal center advanced practice providers, fetal center nurse coordinators, genetic counselors, and more, who work together to provide unparalleled care for patients every step of the way. We collaborate with our colleagues at The University of Texas at Austin and the Dell Medical School to utilize the latest research, diagnostic, and treatment techniques, allowing us to identify new therapies to improve treatment outcomes. We are committed to communicating and coordinating your care with your other healthcare providers to ensure that we are providing you with comprehensive, whole-person care.

Learn More About Your Care Team

Comprehensive Fetal Care Center

Dell Children's Specialty Pavilion

4910 Mueller Blvd. Austin, TX 78723

1-512-324-0040

Get Directions