Fetal Gastrointestinal Obstructions

A fetal gastrointestinal obstruction is a blockage that can occur at any point along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Fetal gastrointestinal obstructions are rare and occur in approximately 1 out of 5,000 live births worldwide.

About Fetal Gastrointestinal Obstructions

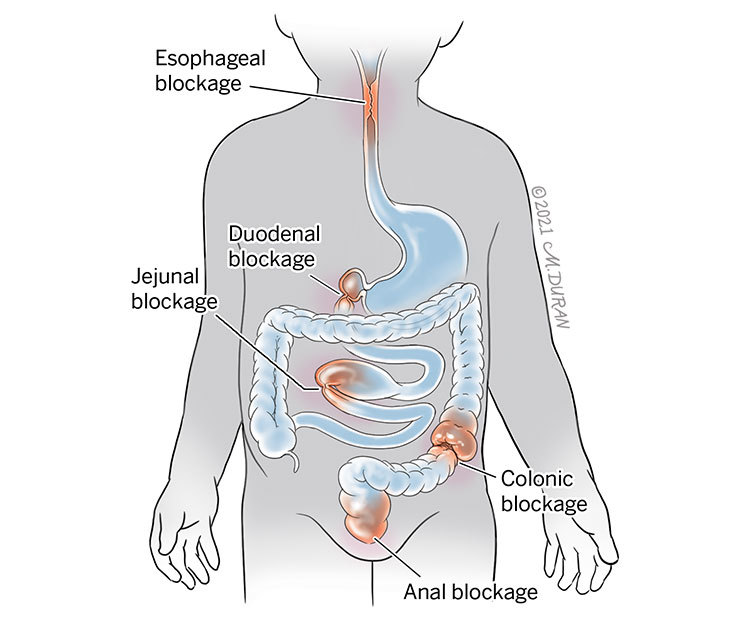

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is comprised of a series of hollow tubes and organs that extend from the mouth to the anus and allow for the digestion of food once a baby is born. Oral liquids and solids are moved through these structures, starting with the mouth and followed by the esophagus, stomach, small intestine (divided into the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum), and large intestine (colon) before ending with the anus. During fetal development, a blockage can occur at several sites along the GI tract. This blockage is more commonly the result of an underdeveloped portion (an absence of a normal opening or failure of a structure to be tubular) of the GI tract (atresia), but the blockage can also be caused by pressure (narrowing or restriction of a blood vessel or valve that reduces blood flow) from an outside structure (stenosis).

The most common types of fetal gastrointestinal obstructions include:

- Esophageal atresia occurs in approximately 1 out of every 4,500 live births and is characterized by a blockage in the esophagus (the tube that leads from the throat to the stomach). This can also be associated with problems in the development of the trachea (windpipe). An abnormal connection in one or more places between the esophagus and the trachea is known as a tracheoesophageal fistula.

- Duodenal atresia occurs in approximately 1 out of every 10,000 live births and is characterized by a blockage in the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine, just past the stomach) that prohibits food or fluid from leaving the baby’s stomach.

- Jejunal atresia occurs in approximately 1 out of every 3,000 live births and is characterized by a blockage in the middle portion of the small intestines (jejunum) in which there is a partial or complete absence of the membrane connecting the small intestine to the abdominal wall (mesentery), causing the jejunum to twist around an artery that supplies blood to the colon (marginal artery).

- Colonic atresia occurs in approximately 1 out of every 20,000 live births and is characterized by a blockage in the lower intestines or large bowel in which part of the colon is completely blocked or missing.

- Anal atresia occurs in approximately 1 out of every 5,000 live births and is characterized by a blockage at the bottom end of the GI tract that prohibits stool from exiting the body due to a lack of opening. Anal atresia can occur in association with atresia of the rectum in which the final portion of the large intestine, just before the anus, does not develop properly. This is known as an anorectal malformation.

Symptoms of Fetal Gastrointestinal Obstructions

Signs of a fetal gastrointestinal obstruction can often be observed on a fetal ultrasound.

Signs of a fetal gastrointestinal obstruction may include:

- An enlarged fetal stomach

- Dilated collections of fluid inside the fetal abdomen

- Fluid inside the fetal abdomen but outside of the bowel (ascites)

- The appearance of calcifications (accumulations of calcium) in the abdomen of the fetus

- The appearance of extra amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios)

Causes of Fetal Gastrointestinal Obstructions

The cause of a fetal gastrointestinal obstruction remains unknown. However, a fetal gastrointestinal obstruction is thought to arise from damage to the blood vessels that feed into the GI tract during the first 6 to 12 weeks of gestation. Bowel obstructions can occur as a result of the twisting of the bowel on itself (volvulus), improper rotation of the bowel in early pregnancy (malrotation), or the sliding of a portion of the bowel into an adjacent portion of the bowel similar to that of a telescope (intussusception). Maternal medications, including some decongestants as well as maternal use of nicotine, amphetamines, or cocaine, have also been associated with bowel obstructions.

Complications Associated With Fetal Gastrointestinal Obstructions

Since the baby gets all of their nutrition from the mother through the placenta while in the womb, an obstruction in the GI tract does not cause any major problems for the fetus. A blockage in the upper parts of the GI tract (esophagus, duodenum, and first part of the jejunum) can often lead to an accumulation of excess fluid that surrounds the outside of the baby in the amniotic sac (polyhydramnios). This happens when amniotic fluid is swallowed or inhaled by the baby but the fluid is unable to be adsorbed properly due to the blockage along the GI tract. While polyhydramnios is not dangerous for the baby or the pregnant mother, it can cause a shortening of the cervix, which may cause premature contractions.

The following forms of atresia are commonly associated with other anomalies:

- Esophageal atresia is associated with other anomalies in over 50% of cases, often occurring due to an abnormal connection in one or more places between the esophagus and the trachea (windpipe) known as tracheoesophageal fistula. Chromosomal problems can occur in up to 10% of cases.

- Duodenal atresia is associated with heart abnormalities in up to 33% of cases. It is also associated with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) in 30% of cases.

- Jejunal atresia is rarely associated with other structural or chromosomal abnormalities. However, it is associated with cystic fibrosis in 10% of cases.

- Colonic atresia is rarely associated with other structural or chromosomal abnormalities. However, it can be associated with missing nerve cells in the muscles of the colon (Hirschsprung’s disease), which makes it difficult to pass stool.

- Anal atresia is associated with other structural or chromosomal abnormalities or genetic syndromes in up to 50% of cases.

Diagnosing Fetal Gastrointestinal Obstructions

Fetal gastrointestinal obstructions are often found at the time of an anatomy ultrasound at around 20 weeks (5 months) of gestation. In some cases, the ultrasound may appear normal at 20 weeks, but a repeat ultrasound later in pregnancy will appear abnormal. Depending on the location of the obstruction, the ultrasound image will look different.

The following forms of atresia are identifiable through fetal ultrasound:

- Esophageal atresia can be difficult to diagnose by early ultrasound. The only sign may consist of a small stomach. A pouch of fluid located at the end of the blocked esophagus may be observed in the baby’s neck later in the pregnancy. Your doctor may order an MRI to better observe the esophagus.

- Duodenal atresia may be identified by a “double bubble” sign on a fetal ultrasound of the fetal abdomen.

- Jejunal atresia may be identified by multiple dilated loops of intestines on a fetal ultrasound of the fetal small bowel. Active movement of these bowel segments is usually identifiable through ultrasound.

- Colonic atresia may be identified by a dilated loop in the large bowel on a fetal ultrasound of the large bowel. Meconium (the green stool that is first passed by a newborn) is usually identifiable in the loop through ultrasound.

- Anal atresia may be identified by a dilated rectum behind the bladder on a fetal ultrasound of the rectum. This dilation is not typically identifiable through ultrasound.

Pregnancy With Fetal Gastrointestinal Obstructions

The main concern for the pregnant mother with a fetus with a GI obstruction is the development of excess fluid in the sac surrounding the fetus (polyhydramnios). In some cases, if the mother is experiencing discomfort or difficulty breathing, this fluid may need to be removed through a procedure known as amnioreduction. During this procedure, a needle is placed into the uterus using ultrasound for guidance. The needle is then connected to a tube and the excess fluid is drained over a 20- to 30-minute period of time. Usually, polyhydramnios does not occur with a fetal gastrointestinal obstruction until at about 32 weeks (8 months) of gestation. Oftentimes, polyhydramnios will return after the initial amnioreduction is performed, causing the need for 2 to 3 amnioreduction procedures before delivery.

After the initial evaluation, you will be scheduled for ultrasounds every 3 to 4 weeks to assess your baby’s rate of growth. If the amniotic fluid is increasing, your doctor may elect to perform ultrasounds weekly to monitor the fluid level. A vaginal probe ultrasound may be performed to assess your cervical length to ensure you are not at risk for premature delivery. Your fetal medicine specialist may order a fetal MRI to observe structures in the fetus that cannot be observed easily with ultrasound.

You will likely also be scheduled for a prenatal consult with a pediatric surgeon since your baby will need surgery after birth. You may also be referred to a genetic counselor to discuss the risk for potential chromosomal problems in your fetus as well as available tests that can be completed to identify the types of problems.

A vaginal delivery is safe for fetuses with all types of GI obstructions. Your doctor may elect to induce you at 39 weeks of gestation (one week before your due date). If you have required several amnioreductions to treat polyhydramnios by the time you reach 37 weeks of gestation (3 weeks before your due date) and it appears that the fluid is worsening, it may be preferable to proceed with an induction of labor instead of performing another amnioreduction.

Treating Fetal Gastrointestinal Obstructions

There are currently no forms of fetal surgery available for fetal gastrointestinal obstructions. All treatments are performed after your baby is born.

Evaluation After Birth

After birth, your baby will be taken to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). A pediatric surgeon will evaluate the baby soon after they are born. Unless there is evidence of injury to the intestines, these conditions rarely require emergency surgery. X-rays and imaging studies may be performed to identify where the obstruction is located along the baby’s GI tract. If necessary, surgery will be performed to correct the problem before the baby is fed. Your pediatric surgeon will counsel you on the type of surgery that will be required for your baby’s condition. Most babies do well after surgical correction of their GI obstruction. Long-term problems are usually related to other anomalies that are associated with the GI obstruction, such as heart and chromosomal problems.

Care Team Approach

The Comprehensive Fetal Care Center, a clinical partnership between Dell Children's Medical Center and UT Health Austin, takes a multidisciplinary approach to your child’s care. This means you and your child will benefit from the expertise of multiple specialists across a variety of disciplines. Your care team will include fetal medicine specialists, obstetricians, neonatologists, sonographers, palliative care providers, fetal center advanced practice providers, fetal center nurse coordinators, genetic counselors, and more, who work together to provide unparalleled care for patients every step of the way. We collaborate with our colleagues at The University of Texas at Austin and the Dell Medical School to utilize the latest research, diagnostic, and treatment techniques, allowing us to identify new therapies to improve treatment outcomes. We are committed to communicating and coordinating your care with your other healthcare providers to ensure that we are providing you with comprehensive, whole-person care.

Learn More About Your Care Team

Comprehensive Fetal Care Center

Dell Children's Specialty Pavilion

4910 Mueller Blvd. Austin, TX 78723

1-512-324-0040

Get Directions