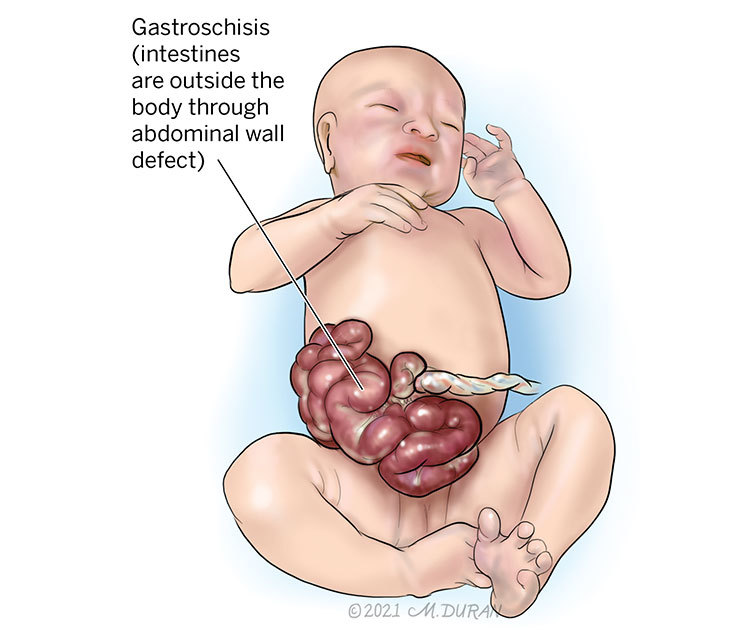

Gastroschisis

Gastroschisis is an abdominal wall defect in which the anterior abdomen does not close properly, causing the intestines to protrude and develop outside the of fetus and in the amniotic sac (the fluid surrounding the fetus). Gastroschisis is rare and occurs in approximately 2 to 6 out of every 10,000 live births in the United States.

About Gastroschisis

At around 6 weeks of gestation, the folds in tissue that form the front abdominal wall of the fetus may not close completely, resulting in an opening or defect in the baby’s belly known as gastroschisis. The hernia (when an internal organ or other body part protrudes through the wall of muscle or tissue that normally contains it) is located to the right of the umbilical cord, allowing the baby’s small intestines, and sometimes the large intestines, to protrude into the fluid surrounding the fetus (amniotic sac). Because the fluid is sterile (no infection is present) and the temperature of the fluid is constant (the same temperature as the pregnant mother), the intestines, although herniated, typically develop normally. On occasion, a blockage in the intestines (intestinal atresia) can occur. An atresia does not present a problem for the fetus since the baby is not using the intestines for food adsorption while in the womb.

Symptoms of Gastroschisis

Signs of gastroschisis can often be detected on a fetal ultrasound. The intestines, and potentially other organs, will be visibly seen outside the body near where the umbilical cord stump (what becomes the navel, or “belly button”) is located after birth.

Causes of Gastroschisis

The cause of gastroschisis remains unknown. However, it tends to occur more often in fetuses carried by young mothers in their teens or early twenties as well as those mothers that smoke.

Complications Associated With Gastroschisis

Gastroschisis is rarely associated with any health risks for the pregnant mother other than the need for a premature delivery if the fetus is not growing properly. However, complications with other organs in a fetus with gastroschisis, although rare, can occur. Intestinal atresia (when a part of the fetal bowel is not developed, causing the intestinal track to become partially or completely blocked) can occur in association with gastroschisis. Some fetuses with gastroschisis may also develop a problem with the slowing of their growth known as intrauterine growth restriction. The reason for this is unclear. A fetus with gastroschisis is at an increased risk (3-5%) for dying in the womb. Most of these cases occur toward the end of pregnancy. Chromosomal abnormalities in fetuses with gastroschisis are also uncommon.

On rare occasions, the herniated intestines found outside of the fetus can twist, causing less blood to be delivered to the intestines, which can result in the death of this portion of the intestines. When these intestines are removed after birth, only a small portion of viable small intestines may remain, which is known as short gut syndrome. This can result in long-term problems for the adsorption of food once the baby is born.

Most babies with gastroschisis do not develop long-term problems. Occasionally, children with gastroschisis may develop a blockage of the intestines that requires hospitalization or even surgery. A higher incidence of inguinal hernias (when tissues, such as part of the intestine, protrudes through a weak spot in the abdominal muscles) has also been reported in these babies.

Diagnosing Gastroschisis

Sometimes, the pregnant mother will undergo a blood test known as an alpha-fetoprotein (AFA) test. This is usually performed to detect spina bifida in the fetus; however, elevated levels of alpha-fetoprotein can also be associated with gastroschisis. Gastroschisis is more commonly found at the time of an anatomy ultrasound at around 20 weeks (5 months) of gestation. A protruding cauliflower-like mass appears on the front side of the fetus, and the umbilical cord is located to the right of the mass.

Pregnancy With Gastroschisis

After the initial evaluation, you will be scheduled for ultrasounds every 3 to 4 weeks to monitor your baby’s rate of growth. At around 32 weeks (8 months) of gestation, you will be scheduled weekly for a biophysical profile. This is an ultrasound test that measures the amount of fluid around the baby as well as how the baby is moving and breathing. The biophysical profile testing may be started before 32 weeks of gestation if problems with the growth of the baby arise. You may also be asked to do a fetal kick count assessment, where you count the number of times your baby moves each night to keep a record. During your pregnancy, you will also be scheduled to meet with a pediatric surgeon who will repair your baby’s hernia after birth.

Typically, most women with a baby in utero with gastroschisis will be induced at around 37 weeks (3 weeks before your due date) of gestation. You may be scheduled to deliver earlier if an ultrasound reveals that the fetus has stopped growing in the womb, the biophysical profile testing reveals the fetus is in distress, or if you report decreased fetal movement. A vaginal delivery is safe for fetuses with gastroschisis.

Treating Gastroschisis

There are currently no forms of fetal surgery available for treating gastroschisis.

Evaluation After Birth

After birth, your baby will be wrapped in a sterile wet towel and the lower half of their body will be placed in a plastic bag to retain heat and moisture. The baby will then be transported to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). A pediatric surgeon will evaluate the baby soon after they are born to prepare for an operation to cover the intestines. In most cases, the intestines can be placed back into the baby’s belly and the opening closed. In some cases, there is not enough room in the baby’s belly; therefore, a silo (covering) is placed over the intestines and secured underneath the skin. Over a few days, the intestines can gradually be returned to the belly. Then, the baby is taken to surgery to remove the silo and close the opening.

Because the intestines will have been located outside of the baby for much of fetal life, the normal movement of the muscles of the intestines may take several weeks to return. Therefore, babies with gastroschisis are only fed intravenously through a method known as total parenteral nutrition (TPN), which allows fluids to bypass the gastrointestinal tract until the baby begins to pass stool. If an intestinal atresia is detected during this time, the baby may require a second surgery to remove the portion of the bowel that is blocked.

Care Team Approach

The Comprehensive Fetal Care Center, a clinical partnership between Dell Children's Medical Center and UT Health Austin, takes a multidisciplinary approach to your child’s care. This means you and your child will benefit from the expertise of multiple specialists across a variety of disciplines. Your care team will include fetal medicine specialists, obstetricians, neonatologists, sonographers, palliative care providers, fetal center advanced practice providers, fetal center nurse coordinators, genetic counselors, and more, who work together to provide unparalleled care for patients every step of the way. We collaborate with our colleagues at The University of Texas at Austin and the Dell Medical School to utilize the latest research, diagnostic, and treatment techniques, allowing us to identify new therapies to improve treatment outcomes. We are committed to communicating and coordinating your care with your other healthcare providers to ensure that we are providing you with comprehensive, whole-person care.

Learn More About Your Care Team

Comprehensive Fetal Care Center

Dell Children's Specialty Pavilion

4910 Mueller Blvd. Austin, TX 78723

1-512-324-0040

Get Directions