Platelet Alloimmunization

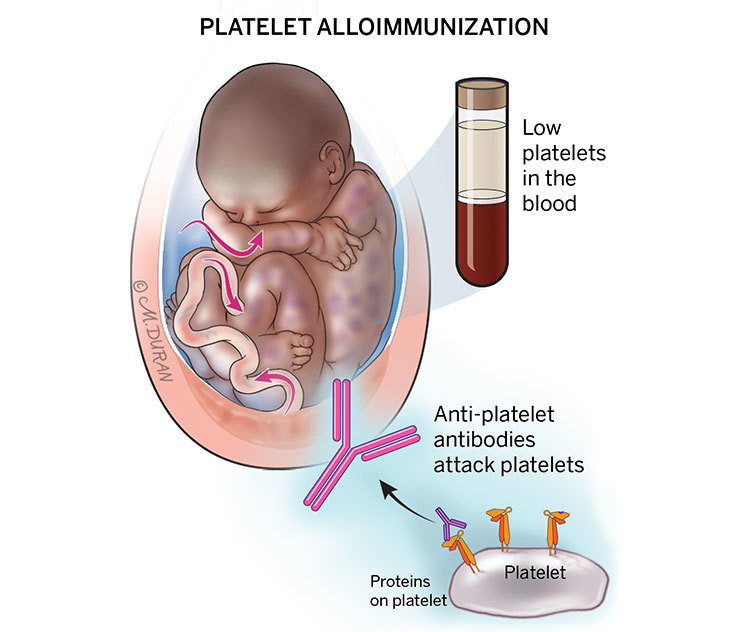

Platelet alloimmunization is an immune response to foreign proteins (antigens) present on the surface of genetically different platelets that have been exposed to the body. Platelet alloimmunization in pregnancy can lead to fetal/neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT), which is a rare condition that affects a baby's platelets and puts the baby at risk of problems for bleeding, particularly in the brain.

About Platelet Alloimmunization

Platelets are the cells in the bloodstream that form blood clots and stop or prevent bleeding when the body is injured. All platelets have natural proteins (antigens) on their surface. In babies, half of these antigens are inherited from the mother and the other half from the father. Due to genetic factors, the mother may have platelets that differ from those of the father. In most pregnancies, this difference does not present a problem. However, in some pregnancies, a baby’s platelets can cross into the mother’s bloodstream at the time of delivery, and when the baby’s platelets differ from the mother’s (due to the father passing his platelet type on to the unborn baby), the mother’s body recognizes these platelets as foreign and forms anti-HPAs (defensive, anti-platelet antibodies). This process is known as platelet alloimmunization.

The most common antibody implicated is anti‐HPA‐1a, but there are other rarer antibody types. The anti-HPAs can cross the placenta and attack the baby's platelets in the next pregnancy. If this happens, the baby's platelets may be destroyed and their platelet count can fall dangerously low, causing fetal/neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT). In some cases of FNAIT, mild bleeding can occur under the skin or tissue just after the baby is born. In severe cases of FNAIT, bleeding can occur in the brain (intracranial hemorrhage) even before the baby is born. While this is very rare, it can have serious effects on the baby's health.

About Platelet Inheritance

On the surface of a platelet there are different types of proteins known as antigens, most of which have been classified as a human platelet antigen (HPA) and designated with a number (1-16) followed by an “a” to represent the more common gene or “b” to represent the less common gene (i.e., HPA-1a or HPA-1b). While 35 HPA antigens have been defined, most testing for differences between the baby’s mother and father involves HPA antigens 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, and 15. Differences in the HPA results for HPA-1, HPA-3, and HPA-5 antigens are most commonly associated with problems in pregnancy. Other differences in platelet types can occur, but these are common and rarely cause problems.

Every person has two copies of genes that form each HPA antigen. One gene type is designated “a” and the other type “b.” A person can carry two of the same gene types or one of each gene type, and the two gene names are separated by a backslash (“/”). For example, a minority of Caucasian women (2%) are HPA-1b/HPA-1b. This means they are homozygous for the HPA-1b gene (the same gene is present on both chromosomes). One can also state that they are HPA-1a negative since they have two copies of HPA-1b. There is a 98% chance that the baby’s father carries the HPA-1a gene. If he carries one copy of the gene, he is HPA-1a/HPA-1b, which is referred to as heterozygous and has a 26% chance of occurring. If he carries two copies of the gene, he is HPA-1a/HPA-1a, which is homozygous. A heterozygous father has a 50% chance of passing on the problem gene, and a homozygous father has a 100% chance of passing on the problem gene.

Symptoms of Platelet Alloimmunization

When anti-platelet antibodies cross through the placenta and attach to the unborn baby’s platelets, this can cause a drop in the baby’s platelet count, causing fetal/neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT).

Symptoms of FNAIT may include:

- Bleeding in the head (as determined with ultrasound)

- Ecchymosis (bruising of the skin due to bleeding underneath the skin)

- Extra bleeding at the time of circumcision in newborn males

- Intracranial hemorrhage (bleeding in the brain), which can occur even before the baby is born

- Petechiae (tiny red dots on the skin due to mild bleeding under the skin from broken blood vessels)

- Purpura (a rash of purple spots due to blood vessels leaking blood into the skin)

Complications Associated With Platelet Alloimmunization

Platelet Alloimmunization is not associated with any health risks for the pregnant mother. While platelet alloimmunization can cause fetal/neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT), as long as there is no evidence of intracranial hemorrhage (bleeding in the baby’s brain), your baby should not experience any long-term problems from FNAIT. In the case of intracranial hemorrhage, the long-term outcome will depend on the size of the bleed and the location of the bleeding inside the skull.

Diagnosing Platelet Alloimmunization

Pregnant women do not undergo routine testing for their platelet type so differences in platelet types between the baby’s mother and father are not suspected unless there has been a previously affected fetus or newborn, in which case the parents are offered blood tests to confirm or rule out platelet alloimmunization. There are many other causes of low platelets in babies, of which the baby or mother may also need to be tested for. As these conditions are rare, expertise is limited to specialist centers and a hematologist and fetal medicine specialist usually perform and interpret the tests together.

Once the diagnosis is suspected, the baby’s mother and father undergo blood testing. The parents’ blood samples are sent to a special laboratory where the platelet types of both individuals are determined using special genetic methods. The mother’s blood is checked for the presence of anti-platelet antibodies. Additionally, the mother’s blood is “mixed” with the father’s platelets to see if there is a reaction, which can also indicate the presence of anti-platelet antibody genes. The baby’s father’s zygosity can also be determined. There is a 72% chance the father is homozygous. If the father is found to be heterozygous, a blood test on the baby’s mother can be ordered to determine if the fetus has inherited the problem platelet antigen, of which there is a 50% chance.

Pregnancy With Platelet Alloimmunization

If platelet alloimmunization occurs or fetal/neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT) is diagnosed, you will be scheduled for ultrasounds every few weeks to assess for evidence of intracranial hemorrhage in your baby. Mothers who have had a baby with mild FNAIT are typically scheduled for delivery at around 37–38 weeks of gestation (2 weeks before your due date). Pregnant mothers who have had a baby with intracranial hemorrhage or moderate to severe FNAIT are typically scheduled for delivery at around 35–36 weeks of gestation (5 weeks before your due date).

Some mothers are willing to undergo a sampling of blood from the fetal umbilical cord to determine whether the fetal platelet count is normal. During this procedure, a needle is inserted in the uterus and into the umbilical cord to obtain a fetal blood sample. This procedure is associated with a risk for slowing of the fetal heart rate, which can result in the need for an emergency C-section, as well as a risk for bleeding from the cord if the fetal platelet count is low. Most pregnant mothers do not want to take these risks and choose to deliver by C-section.

You may be asked to donate platelets several days before your planned delivery, in which case you will be put on a special machine that draws your blood from one arm and separates the platelets from your drawn blood before returning the blood (your red and white blood cells) to your body. These platelets are useable for about a week, and if your baby is born with a low platelet count, your platelets will be washed to remove any of your antibodies and given to your baby. Sometimes, because your own platelet count may be too low or if there isn’t enough time to arrange a platelet donation, a special blood donor will be used to ensure your baby receives the correct type of platelets they need.

Treating Platelet Alloimmunization

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is an effective treatment for the vast majority of fetal/neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT) cases. IVIG contains the immunoglobulins (antibodies) from plasma of over 1,000 blood donors. All donors have been tested for hepatitis and HIV, and none of these infections have been reported in patients who have received IVIG. This “blood product” is given intravenously through a drip over a span of 6 hours every week to pregnant women at risk of FNAIT. IVIG may be initiated as early as 12 weeks (in some cases with a previous history of severe FNAIT) and continued until birth at around 36–37 weeks (8 months) of gestation. The first dose of IVIG is usually administered in the hospital followed by one to two visits per week by a home visiting nurse for the remainder of the pregnancy. The primary risk of IVIG is severe headache, which can usually be controlled by increasing the amount of fluid you are given before and after the IVIG in conjunction with various medications. IVIG has been associated with a decreased blood count (anemia) in patients with type A, B, or AB blood. If this pertains to you, your doctor may elect to check your blood counts every few weeks. The FDA has put a package label on IVIG to indicate that it has been associated with strokes and blood clots; however, these have not been reported in pregnant women receiving this therapy.

Pregnancies with a history of FNAIT in a previous gestation are usually treated with a combination of IVIG and oral steroids. Oral steroids in high dosage are associated with weight gain, mood disturbances, and sleep disorders as well as with an increased risk for gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia (high blood pressure) in pregnancy.

The timing and dosage of IVIG and steroids are based on the degree of problems in your previous pregnancy.

Previous pregnancy with low platelet count in the newborn:

- 20 weeks of gestation: Initiate weekly IVIG with oral steroids

- 32 weeks of gestation: Increase IVIG to twice weekly

Previous fetus or newborn with intracranial hemorrhage at or greater than 26 weeks of gestation:

- 12 weeks of gestation: Initiate weekly IVIG

- 20 weeks of gestation: Increase IVIG to twice weekly

- 28 weeks of gestation: Add oral steroids

Previous fetus with intracranial hemorrhage at less than 26 weeks of gestation:

- 12 weeks of gestation: Initiate IVIG twice weekly

- 20 weeks of gestation: Add steroids

These treatments may still result in the birth of a baby with a low platelet count. Depending on how your previous pregnancy was affected, the chance for an intracranial hemorrhage even with proper treatment is at around 8%.

Evaluation After Birth

After birth, your baby will likely be taken to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for monitoring. A platelet count will be drawn from your baby to see if their count is low. If it is below 50,000, your baby will likely be given platelets from you or another donor. After receiving the donor platelets, your baby’s platelet count will continue to be monitored to ensure that it increases. A neonatologist may order an ultrasound of the baby’s head to rule out any evidence of bleeding.

Care Team Approach

The Comprehensive Fetal Care Center, a clinical partnership between Dell Children's Medical Center and UT Health Austin, takes a multidisciplinary approach to your child’s care. This means you and your child will benefit from the expertise of multiple specialists across a variety of disciplines. Your care team will include fetal medicine specialists, obstetricians, neonatologists, sonographers, palliative care providers, fetal center advanced practice providers, fetal center nurse coordinators, genetic counselors, and more, who work together to provide unparalleled care for patients every step of the way. We collaborate with our colleagues at The University of Texas at Austin and the Dell Medical School to utilize the latest research, diagnostic, and treatment techniques, allowing us to identify new therapies to improve treatment outcomes. We are committed to communicating and coordinating your care with your other healthcare providers to ensure that we are providing you with comprehensive, whole-person care.

Learn More About Your Care Team

Comprehensive Fetal Care Center

Dell Children's Specialty Pavilion

4910 Mueller Blvd. Austin, TX 78723

1-512-324-0040

Get Directions